Rebecca Frecknall has taken a bold approach to reviving classics from the American theatre repertoire, often injecting fresh spins into the narrative. However, her direction of Eugene O’Neill’s last play, A Moon for the Misbegotten, surprises by leaning towards a straightforward interpretation.

This faithful approach starkly reveals the play’s dated elements, which occasionally feel cumbersome. The production itself lacks balance and drags for three hours, failing to build momentum and instead meandering towards an unsatisfying conclusion.

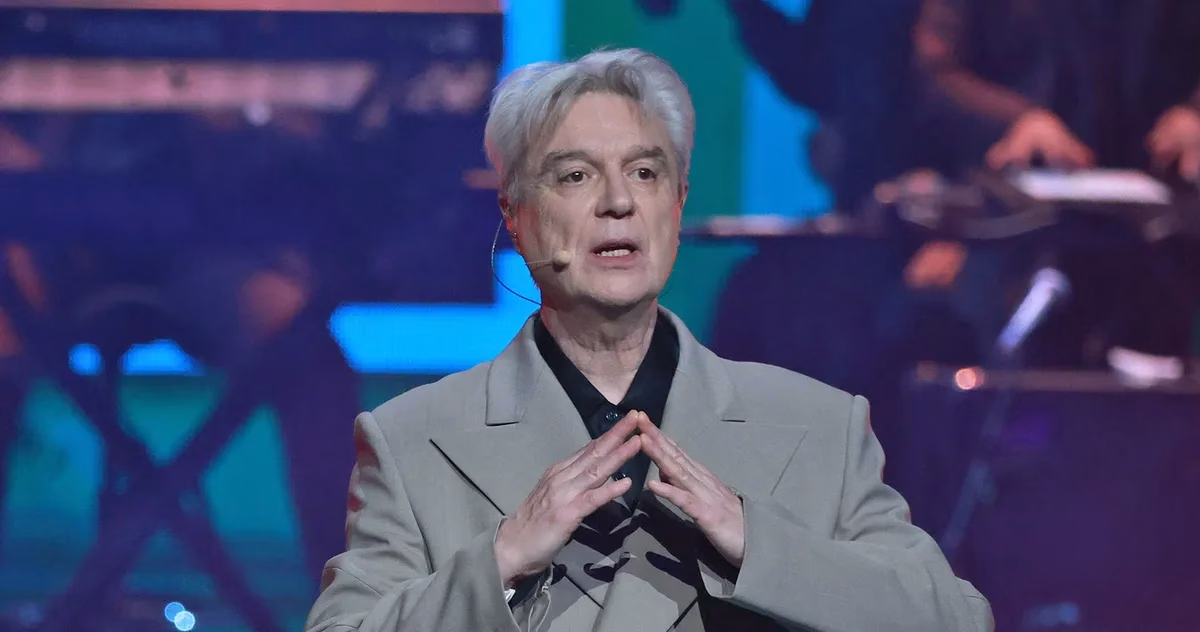

The plot revolves around the troubled farmer Phil Hogan (played by David Threlfall), who hatches a plan for his daughter, Josie (Ruth Wilson), to seduce the wealthy landowner James Tyrone (Michael Shannon) as a means of blackmail to save their family farm. In a moonlit night filled with flirtation, tension, and conflicting emotions, Josie and James seem to be stuck in a repetitive loop rather than moving toward a meaningful resolution. By the play’s conclusion, aspects of their relationship reveal a hint of vulnerability, but it takes far too long to get there.

Ruth Wilson captivates audiences with her strong stage presence, effortlessly embodying Josie’s character with a touch of Irish inflection in her American accent. David Threlfall convincingly portrays the flawed, obstinate father. Nonetheless, the characters often vacillate between being roguish, melodramatic, and tragic, trapped in self-serving monologues that hinder any real psychological progress. The set design by Tom Scutt feels stagnant, depicted through a monotonous beige wash of wood and ladders, stripping the space of intrigue that its exposure could have provided.

As with O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night—to which this play serves as a sequel—the struggle between illusion and reality is paramount. James, the heavy-drinking city dweller, discloses deeper layers of sorrow, while Josie, the town’s scandalous figure, grapples with her sexual reputation and virtue. However, her story often feels overshadowed by James’s emotional turmoil and his troubling “madonna/whore” complex that drives their interactions.

The play also explores themes of female sexuality, defined by the men around Josie, who view it either as a menace or as a bargaining chip. Josie’s physicality is objectified and women are derogatorily labeled, creating an uncomfortable sense of antiquated moral judgment that permeates the narrative. The drama culminates in what appears to be Josie’s transformation into a maternal figure for James’s suffering: “Mother me, Josie, I love it,” he implores, and she reciprocates. One is left to question whether O’Neill intended this to be Josie’s moral lesson.

Ultimately, much of the play carries a sense of anachronism that detracts from its impact. While Frecknall has faced criticism for potentially being overly controlling in her direction, this production could have greatly benefited from a more dynamic and adventurous reimagining.

Running at the Almeida Theatre in London until August 16th.