The Brant Foundation in New York hosts an impressive selection of works by Glenn Ligon, a prominent figure in contemporary art. Curated by the foundation, this exhibition is less a comprehensive dive into the artist’s career and more a concise overview that fosters a connection between the works and the viewer. Featuring eight pieces from the Brant collection spread across four floors, the display showcases Ligon’s “greatest hits,” from stenciled text paintings to neon signs and a video installation. The exhibition is on view through July 19 at the Brant Foundation in the East Village (421 East 6th Street, East Village, Manhattan).

A Journey Through the Boundaries of Language

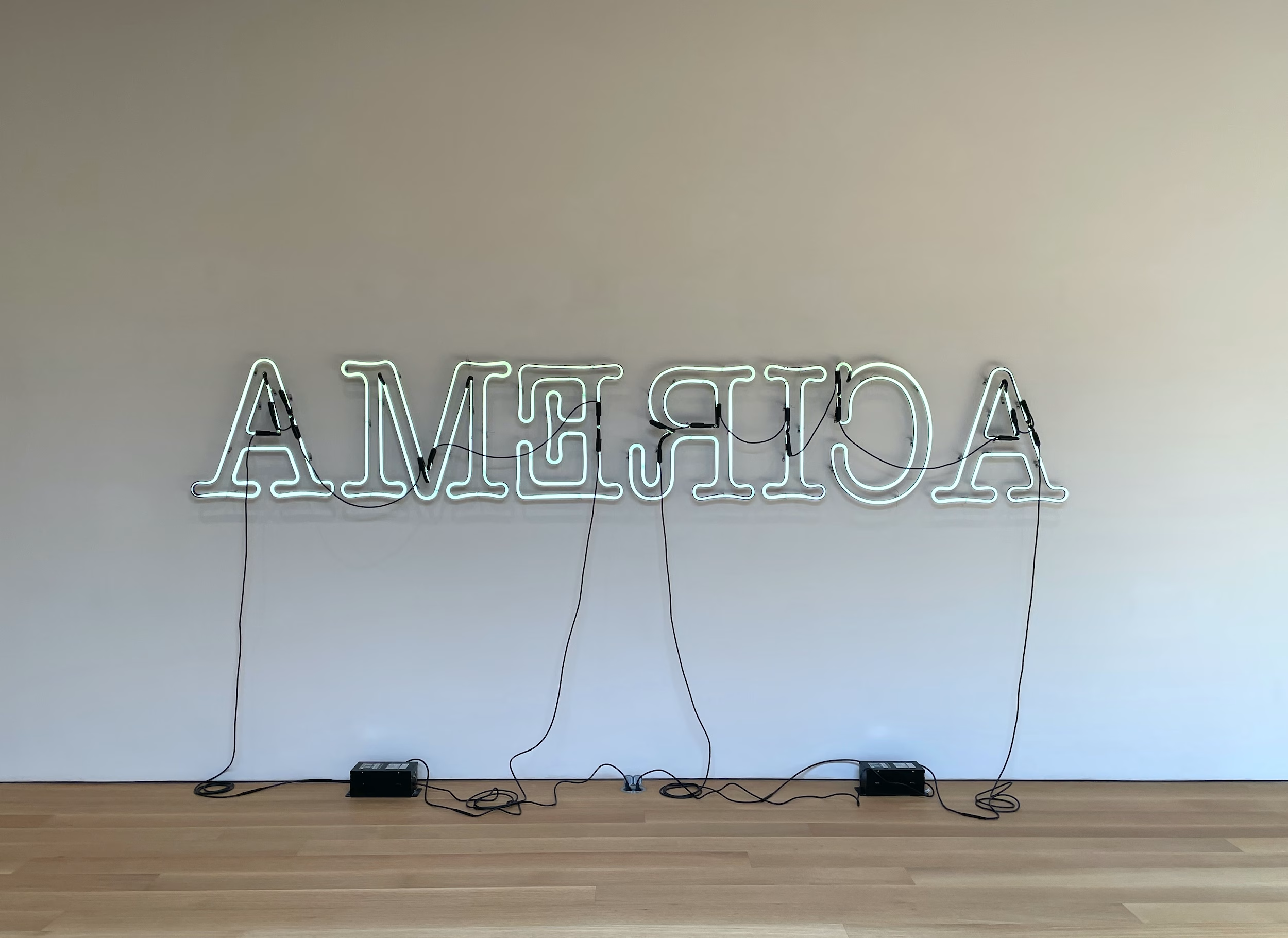

The suggested starting point for the exhibition is the floor featuring Ligon’s iconic text painting Rückenfigur (2009). The title references a technique often associated with Caspar David Friedrich, depicting a figure from behind to invite viewers to project themselves into the scene and reflect. Ligon’s piece—a white neon sign spelling “America” in reversed letters—evokes, in relation to the title, an image of a White America turning its back on others. Yet, Ligon’s use of language transcends a singular, straightforward interpretation. His approach reveals language’s inadequacies and the viewer’s role in interpreting what is said, questioning its legibility.

On an adjacent wall, the text painting Deferred (Malcolm/Martin) (1991) alternates the names “Malcolm” and “Martin” in black against a red background. As the repetition transforms the names into sounds, they visually deteriorate toward the bottom of the canvas, becoming nearly illegible. This underscores that language is not just words but a visual and auditory experience.

The Power of Silence and the Fragmentation of Representation

The exhibition pushes the boundaries of language further with works like Stranger #64 (2012). Drawing from James Baldwin’s 1953 essay “Stranger in the Village,” the illegible text is transformed into a tangible object through layers of oil, acrylic, and coal dust. What initially appears as an aesthetically appealing dark gray surface becomes a disquieting embodiment of Baldwin’s experience of racism in a small, all-white Swiss town.

The most distinct work in the show is Live (2014), a seven-channel, silent video installation. This piece projects footage from comedian Richard Pryor’s 1982 stand-up film Live on the Sunset Strip. Given Ligon’s prior use of Pryor’s material in text-based works, seeing Pryor here—fragmented across screens showing only his face, arm, torso, or groin, without sound—is striking.

Anyone familiar with Pryor knows that racism was a recurring theme in his comedy, much like in Ligon’s art. By fragmenting Pryor’s image, Ligon may be alluding to the fragmentation and fetishization of the bodies of many people of color. Yet, the interpretation isn’t entirely clear-cut. Ligon presents Pryor’s performance through gestures and body language, often displaying submissive or pained expressions rather than comedic ones. This silent observation creates a disquieting yet profoundly meaningful work that fails to communicate conventionally, actively engaging the viewer. Ligon poses the question, “How much can we see of someone speaking without hearing them?” confronting us with language’s limitations and the power of silence.

Glenn Ligon’s exhibition offers a powerful and thought-provoking experience, delving into the layered nature of language, representation, and identity.