The Mad Twelfth Night Revelry That Takes Over Bankside Every January

In the first days of January, London divides into two: one group scours the shops in pursuit of sales, while the other joins a ritual on Bankside—amid leaves, bells, cider, and masks—that gently pushes the boundaries of reason. At the heart of this second group stands a single figure: the Holly Man.

For nearly thirty years, David Risley has brought this role to life, preparing his winter wardrobe not in shopping centres but in park corners, urban green spaces, and at the bases of trees. His costume, woven from pine branches, ivy, and holly, is bold enough to make even Lady Gaga green with envy. In Risley’s words, the costume is not “sewn”; it grows from whatever the season offers.

The Urban Cousin of the Green Man

The Holly Man portrayed by Risley is an urban reflection of the ancient figure from English folklore, the Green Man. He represents new growth, the cycle of nature, and renewal. Every year, on the weekend closest to Twelfth Night, he appears in Bankside—around the Globe Theatre.

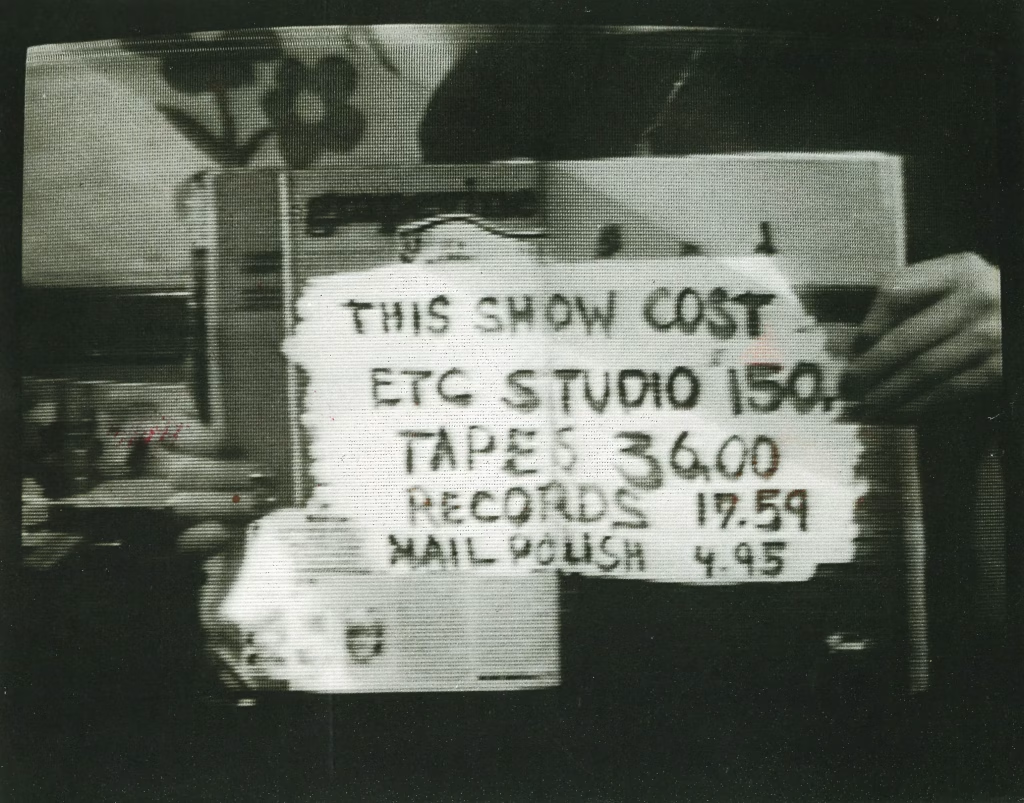

The tone of the ceremony is clear from the very first moment: this is neither a full theatre play nor “just entertainment.” Ancient medieval winter rituals blend with contemporary performance, creating an atmosphere that is both warm and slightly disorienting.

Cider, Songs, and a Sacred Soaking

Accompanied by Beelzebub, the Holly Man advances across the Millennium Bridge toward Bankside as the crowd joins him. Then the wassailing begins: cider is drunk, and the bounty of the new year is celebrated. Traditionally, cider is poured onto the roots of fruit trees; in the Bankside version, the doors of the Globe Theatre are “soaked” with the drink. This is exactly how urban folklore is born.

Risley describes the role like this:

“I’m not a character; I’m more like a being. Like a god standing on the earth, coming from nature and melting back into it.”

A bearded man dressed in red, a bit like Santa, performs in an outdoor play

Mummers’ Play: Chaotic Yet Deep-Rooted

The stage is then set at Bankside Jetty. The mummers’ play begins. Characters like Turkey Sniper, Clever Legs, and Old ’Oss may at first glance seem like a Monty Python or The Mighty Boosh sketch, but their roots stretch back to the Crusades era—a free interpretation of the St. George and the Dragon story.

Everything feels improvised, yet it carries a memory repeated for centuries.

A Slice of Cake, a Crown

As the crowd moves on, the play passes to the audience. Cakes are passed around; whoever finds a bean or pea in their slice is immediately crowned: King Bean or Queen Pea. The procession then heads to Soap Yard in Borough Yards. Amid wine, stories, and dancing, the day melts away. Everyone, including children, is part of this revelry.

This is why Bankside Twelfth Night is so vibrant that it makes even classic Morris dancing seem overly serious.

Masked musicians parade along Bankside

The Human Face of a Tradition

A small anecdote Risley shares sums up why this event still lives on: Over the years, he remembers a woman who limped over every Twelfth Night to bring him a beer. She never introduced herself, only saying, “I’m nobody, but you are somebody.” Then she would disappear. But the ritual continues.

What You Need to Know

Twelfth Night Bankside 2026

In front of the Globe Theatre, Bankside

Sunday, 4 January

From 12:00 onwards

Free, open to all, including children

A Note from Apartment No: 26

Watching this event isn’t enough. Before long, you’ll find yourself singing along, a warm cider in hand, lost in the crowd. The true power of Twelfth Night lies right here: in drawing the audience into the ritual itself.