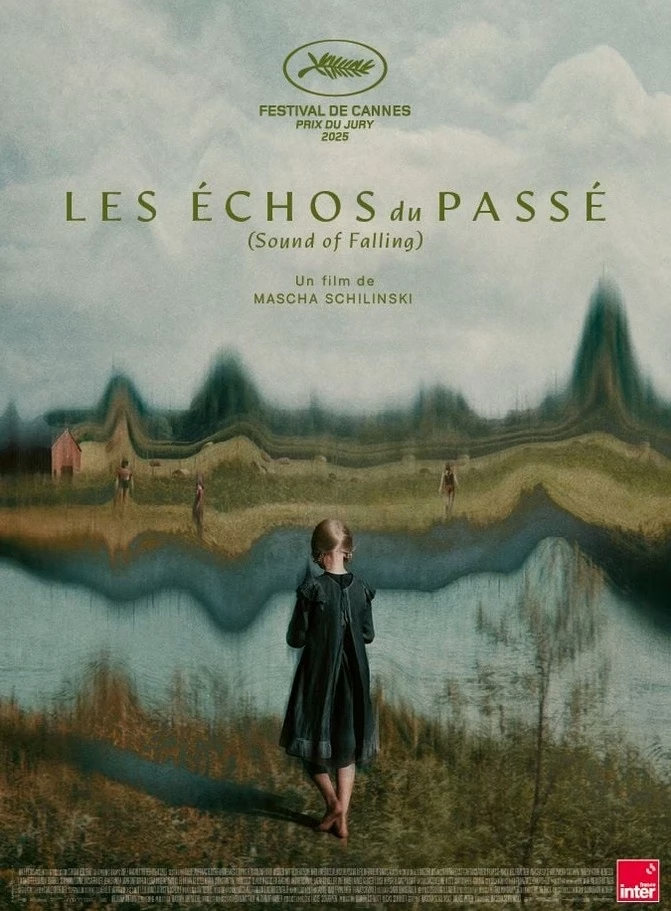

Silent Screams Seeping Through the Cracks of Time: Sound of Falling (2025)

Still echoing through the corridors of 2026 cinema is a film that traps the viewer not merely in a seat, but inside a centuries-long pang of conscience: Sound of Falling. When Mascha Schilinski returned from the 2025 Cannes Film Festival with the Jury Prize, we knew she would upend the beloved yet dusty German “Heimatfilm” genre from its very roots. In this masterpiece, Schilinski replaces pastoral nostalgia with a dark magical realism, transforming a single farmhouse into a trauma chamber where four generations have been silently buried.

At the heart of the film are four women who share the same farmhouse in the Altmark region across a century: Alma, shadowed by the First World War; Erika, amid the ruins of the Second World War; Angelika, trapped in the oppressive grey tones of East Germany; and Lenka, searching for her path in today’s fractured world. Rather than narrating their stories in conventional chronology, Schilinski folds time like a sheet of paper. This non-linear structure forces the viewer to piece together a puzzle, while delivering a slap-in-the-face realization of how one generation’s wound reappears as a “visual rhyme” on the face of the next.

The visual language is the film’s most powerful—and most suffocating—weapon. The narrow 1:1.37 frame ratio makes us voyeurs into the characters’ intimacy, like an X-ray. The camera slips through doorways, lingers at window edges, or peers from dark corners, mimicking the curious gaze of a child discovering hidden violence. This constriction reinforces the reality that the farmhouse is not a refuge, but a dungeon that confines and controls the female body. With dialogue reduced almost to nothing, the film surrenders to a sensory storm: the smell of hay, racing heartbeats, whispers trapped between walls—where words fail, trauma begins to speak in its own language.

Why has Sound of Falling become such a major cultural phenomenon in 2026? The answer lies in today’s “therapy culture” and heightened awareness of intergenerational trauma. We now understand that the silence of our ancestors remains knotted in our own voices. Schilinski reads history not through grand wars and political upheavals, but through bruises hidden in the kitchen, forced sterilizations, and muffled screams. In this sense, the film goes beyond historical reckoning to draw a cinematic map of somatic memory.

Produced under the ZDF and Das kleine Fernsehspiel model—which demonstrates how boldly a public broadcaster can embrace artistic risk—this film stands as the strongest proof that arthouse cinema can achieve greatness without commercial compromise. Its 155-minute runtime and experimental structure, which deliberately pushes the viewer out of their comfort zone, have earned it a place on the Oscar shortlist—not as a film everyone “loves,” but as one that leaves everyone who watches it irrevocably changed. With an ethereal, vulnerable aesthetic reminiscent of Francesca Woodman’s photographs, Schilinski brought German cinema back to Cannes’ most prestigious stage after an eight-year absence, asking us all the same question: Is the place we call home a shelter we hide in, or a tomb we share with the shadows of our ancestors?

This film is not merely a viewing experience; it is a confrontation felt down to the bone. Sound of Falling is not the story of a fall, but of the centuries-long echo of that fall. If you have ever wondered what lies beneath a family’s silence, or how a place can hold memories hostage, this film invites you into those hazy rooms where time and pain are hopelessly intertwined.