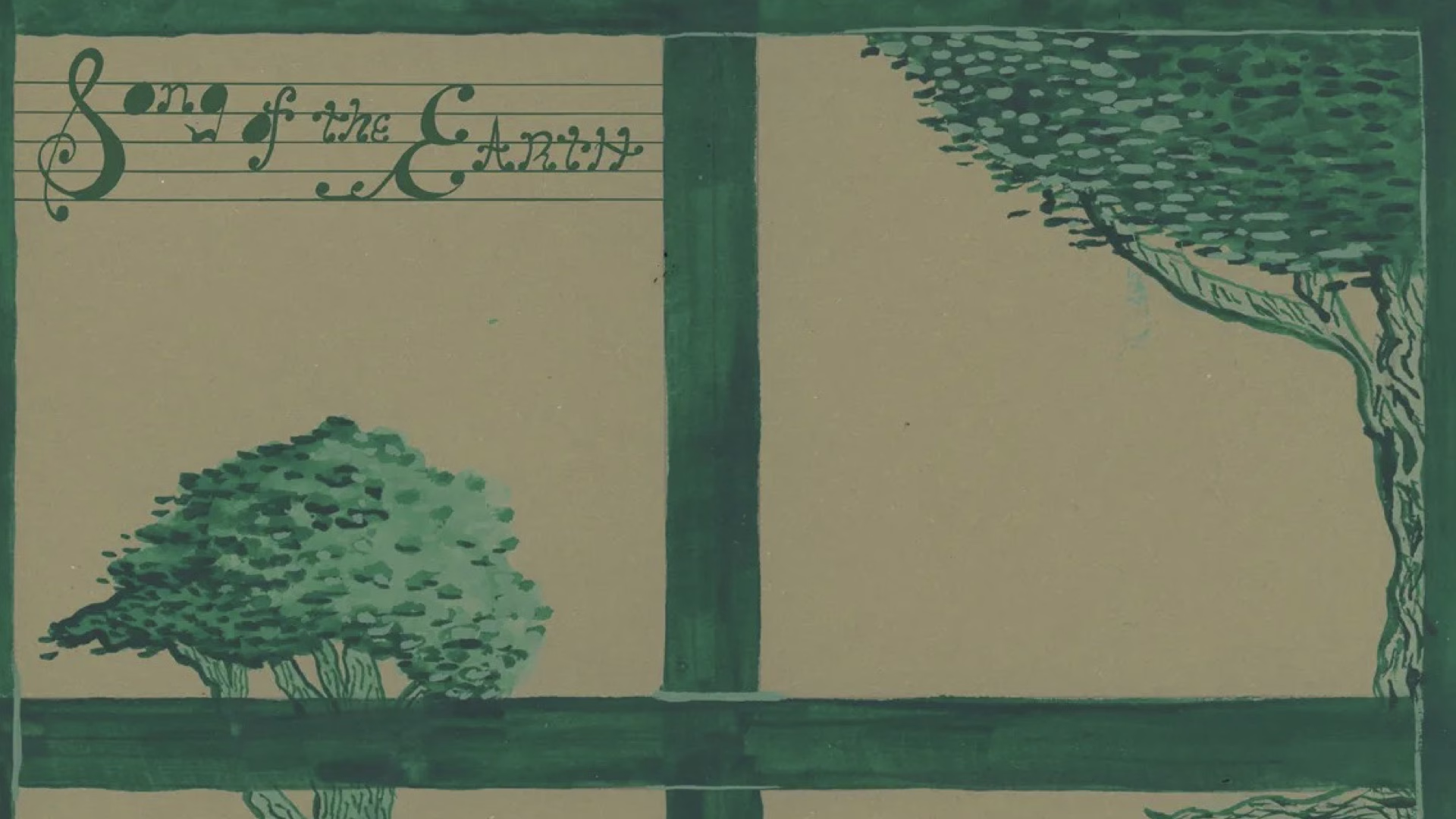

Music Discovery of the Day: David Longstreth, Dirty Projectors ve s t a r g a z e’s 2025 “Bittersweet Symphony”

In the 1960s, Stewart Brand asked NASA a deceptively simple question:

“Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?”

That question ignited both the environmental movement and modern cultural awareness, paving the way for the images that changed everything: ATS-3’s first shot of Earth as a blue sphere and Bill Anders’ Earthrise. These were humanity’s first moments of seeing itself from the outside.

Today, that perspective is no longer enough.

The ecological crises of the 21st century are no longer spectacular visible catastrophes; they are insidious: microplastics, climate migration, chemical traces, slow-burning warming…

This is precisely why Alec Hanley Bemis argues that David Longstreth’s Song of the Earth project offers a new way of seeing.

Where photography once abstracted the world, music now makes it concrete again.

A New Circle Drawn Between Nature and Human

Song of the Earth is a monumental collaboration between Dirty Projectors leader David Longstreth and the European chamber ensemble s t a r g a z e. Nearly 40 musicians are involved, yet instead of orchestral grandeur we feel microscopic intimacy:

The march of a single piano

The haze of a saxophone

The cracked, breathing presence of a human voice

Especially in “Spiderweb at Water’s Edge,” the music creates a sensitivity so delicate it feels as if we are watching a spider’s web glisten. Longstreth’s music does not begin with Earth seen from space; it begins with light on a leaf, with the smell at the water’s edge.

Mahler’s Legacy, Ligeti’s Shadow, and Post-Pandemic Anxiety

The album borrows its title from Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, but aesthetically it leans far more toward the fragility of the 2020s and the thoughts born in lockdown.

There are sudden cosmic moments appear:

In “Twin Aspens,” for instance, Phil Elverum (Mount Eerie) speaks as if encountering a monolith. Yet all that cosmic openness folds back into the human:

“And I saw the dream in the wide sky come in close.”

Even looking outward ultimately becomes looking inward.

The Terrifying Truth of the Earth: “It is worse, much worse, than you think.”

A breaking point arrives with “Uninhabitable Earth, Paragraph One.”

When text from David Wallace-Wells’ book merges with Longstreth’s voice, we confront the harshest reality of the modern world:

“The idea of a slow-moving climate crisis is a fairy tale.”

Here the music drags the story that began in nature’s serenity back to the parking lot beside the highway, just like humanity’s own existential contradiction.

Humanity’s Small, Funny, and Terrifying Traces

Throughout the album, people appear as if they have accidentally stumbled into a landscape:

“Gimmie Bread” and “Bank On” poke at the absurdities of capitalism.

“Opposable Thumbs” reminds us that these hands are the root of the entire catastrophe.

In Longstreth’s vision, the human figure emerges from the bushes as a creature that is simultaneously harmful and fragile, creative and destructive, then vanishes again just as quickly.

The Window the Pandemic Opened: From Inside to Outside, Outside to Inside

Longstreth wrote this work during the pandemic.

Song of the Earth therefore feels like a warning from a time traveller: a whisper that today’s silent disasters will become tomorrow’s loud realities.

As Alec Hanley Bemis puts it:

“When the album ends there is blood, sweat, and rain.

Hope is only possible if we move.”

Apartment No. 26 Verdict

Song of the Earth proposes a new environmental narrative for our age:

Instead of the sterile environmentalism that gazes from space,

an ecology that bends down to the ground, touches the leaf, breathes deeply.

This music is less a warning than a reminder:

The Earth is not an image to be viewed from afar; it is the living organism we inhabit, are part of, and feel.

And perhaps what we need most right now is hidden in these lines:

“Apocalypse is a phase.

It’s hope that saves the day.”